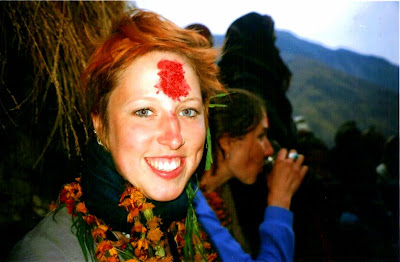

|

| Doctors for Nepal's team preparing to interview patients in Manma Hospital |

Whilst we were doing the family planning assessment in Lalit's village, there being no doctors around, Lalit and I were summoned to the health post to see a sick woman. Given the complex nature of her illness, I could not offer her any treatment in the small shack we were sitting in. I advised the family that she was very ill and if she was to have any hope of survival, she needed to be taken to the closest hospital - 3 days travel away. Her family are unlikely to have the means to be able to fund her transport or treatment and I think it likely that she would have died at home or en route to the hospital.

Nepal is one of the poorest countries in the world and this is reflected in the health of the population. Life expectancy is much lower than that in the West - it is currently 59 compared to 85 in the UK. People die younger, of treatable conditions such as pneumonia or diahorrea.

|

| Dr Kate Yarrow and Rebecca Brady interviewing a women in Mugraha |

Most of us on our trek to Kalikot experienced some gastro-intestinal disruption of one kind or another but we were lucky enough to have access to our own medicines; we are also well nourished meaning a few days of diahorrea would not kill us.

Dying from this kind of condition is reality for many Nepalese. The data we collected in Kalikot revealed that 15 percent of the children born had died in infancy or childhood; mostly from treatable conditions. There is only one doctor in the district which counts 123,000 inhabitants. For a majority of the district's population, this doctor is many days' walk from where they live. By the time the patient reaches the doctor, he or she is often too sick to be treated and dies.

|

| Too many children often stops parents from providing adequate healthcare for them children. |

Patients often do not access health care as they are so poor that they cannot afford the simple medicines to treat them. Another problem they face is, that with so many children to care for, there is no one to take sick children to hospital so they die at home before help can be called.

|

| Maghraj acting as translator for our interviews |

Whilst trekking these last two weeks, I have seen how tourism has brought money into rural areas. The health posts I have visited are impressive examples of what money, education and dedication can do to improve rural health care in the Khumbu (Everest) region. 95 percent of pregnant ladies, for example, are accessing ante-natal care thanks to tourists' donations. However almost every other region of Nepal is lagging far behind.

|

| Dr Kate Yarrow and Christine Bottine interviewing a woman about her use of family planning |

Doctors for Nepal cannot overcome the geographical difficulties of Nepal nor change health seeking behaviour of the country as a whole. We hope that by providing scholarships to medical students who will then work in rural areas, some of these families may go on to live healthier and longer lives. By donating to our charity you will be helping young student doctors to achieve their goal. You will also be supporting health care projects in remote areas.

I hope that by reading this you feel inspired to make a difference. Please donate generously.

NEXT:

The Results: Education levels in Kalikot: Male 64% vs Female 20%

I hope that by reading this you feel inspired to make a difference. Please donate generously.

NEXT:

The Results: Education levels in Kalikot: Male 64% vs Female 20%